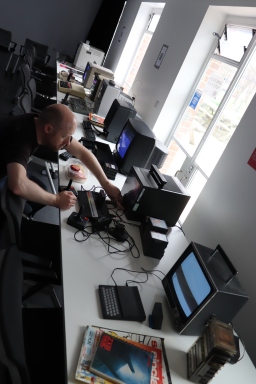

Last week the Sussex Humanities Lab played host to a pretty special experiment. Alex Peverett and Andrew Duff assembled over twenty gaming systems, spanning over forty years of gaming history.

In attendance, says Alex, were such marvels and horrors as a Sinclair ZX81, Atari 2600, Colecovision, Vectrex, Sinclair 128k, Commodore 64, Atari 800XL, Acorn BBC Model B Microcomputer, Windows/Dos Laptop, Nintendo 64, Super Nintendo, Nintendo Gamecube, Sony Playstation 2, Sega Megadrive, Sega Dreamcast, Nintendo Gameboy, Sony PSP, Sony PS4 and PSVR, and a Speak and Spell … that he can remember.

I am fairly sure there were at least one or two systems from a parallel universe’s timeline (but my memory is a bit blurred by vast steam clouds billowing from the polished brass and stained glass Sega Steamcast, so maybe not).

Tim Jordan, Professor of Digital Cultures at Sussex, kicked things off with a highly suggestive, whistlestop tour of issues in gaming from a broadly media studies, sociological, and cultural studies perspective. Tim used the example of a massively multiplayer online roleplaying game to illuminate at least four themes. First, there was the negotiation of meaning and identity in gaming, especially thinking about race, gender, and sexuality. Second, the co-production of games by players, not only through their in-game behaviours, but also through player co-operation outside of games, and the modification and changing of games by players. Third, there was the media archaeology of games, both in regards to the glittering array of stand-alone games surrounding us, and on the servers of discontinued MMORPG. Some digital ludic worlds have an uneasy, precarious existence, liable to have the plug pulled by the owners of the IP. Then Tim wrapped up by looking at some issues around gaming and the digital economy more generally. The older consoles in the room were built with the expectation that players would purchase and fully and permanently own each new game; more recently, gaming has been reshaped by the economics of free-to-play games (with in-game purchases), subscription models, and so on.

Then we played. I tried out a VR game for the first time (and am presumably still in the game, which was Moss). It wasn’t nearly as immersive as I’d been led to expect by commercial hype and popular culture portrayals of VR, but it was fetchingly unsettling. I liked the way sometimes an invisible object or person in the “real” world got in your way, and you just had to push it or them over to pursue your in-game objectives.

I drew some eldritch granite water lilies up from the deep, and helped my heartbreakingly brave protagonist (a needle-wielding champ with a real Reepicheep / Mattimeo vibe) hop across the water. In the background, the mountainous gloom shifted … it was a deer, stooping to drink.

But although I was there for almost the full three hours, I probably only spent ten minutes on the gizmos, because I just kept having nice chats with people! We talked about gaming — video games, board games, tabletop RPGs, gamification, art with game elements, worldbuilding and storytelling across games and other forms of culture. Networking was part of the event’s rationale:

This event will not only be a chance to explore SHL’s media archaeology resources, reflect on media archaelogical theory and practice — and play some games! — but also an opportunity to meet others across the university involved in gaming, game studies, and game design, and to take stock of the state of the art and the future of game studies at Sussex. […] What are we already doing around games at Sussex? How can we bring together existing research and teaching around gaming to share resources, projects, ideas, and opportunities?

We were here to shoot zombie Nazis, but more fundamentally, to shoot the breeze.

For some reason, I did start to think of Sam Ladkin, Senior Lecturer in Critical and Creative Writing (English), as a sort of console. “You should give this one a go,” I told everyone. “It’s really weird.”

Among other things, Sam and I discussed the new elective undergraduate module he’ll be launching, Video Games: Critical and Creative Writing. It sounds like a really fascinating and exciting mix, which will look at games as both technical and cultural objects, will allow students to be assessed through creative work and/or their critical studies of games, and will place politics at its very heart.

With the launch of Video Games: Critical and Creative Writing, along with what’s already happening on the Games and Multimedia Environments BSc and elsewhere, and the outlines of SHL 2 beginning to wobble on the horizon, we could well be at the dawn of a golden age of game studies at Sussex.

(But then again, maybe I’m still in the game).