This week Louise Falcini gave us an update on the AHRC-funded project The Poor Law: Small Bills and Petty Finance 1700-1834.

The Old Poor Law in England and Wales, administered by the local parish, dispensed benefits to paupers providing a uniquely comprehensive, pre-modern system of relief. The law remained in force until 1834, and provided goods and services to keep the poor alive. Each parish provided food, clothes, housing and medical care. This project will investigate the experiences of people across the social spectrum whose lives were touched by the Old Poor Law, whether as paupers or as poor-law employees or suppliers.

The project seeks to enrich our understanding of the many lives touched by the Old Poor Law. This means paupers, but it also means workhouse mistresses and other administrators, midwives, tailors, cobblers, butchers, bakers, and many others. Intricate everyday social and economic networks sprung up around the Poor Law, about which we still know very little.

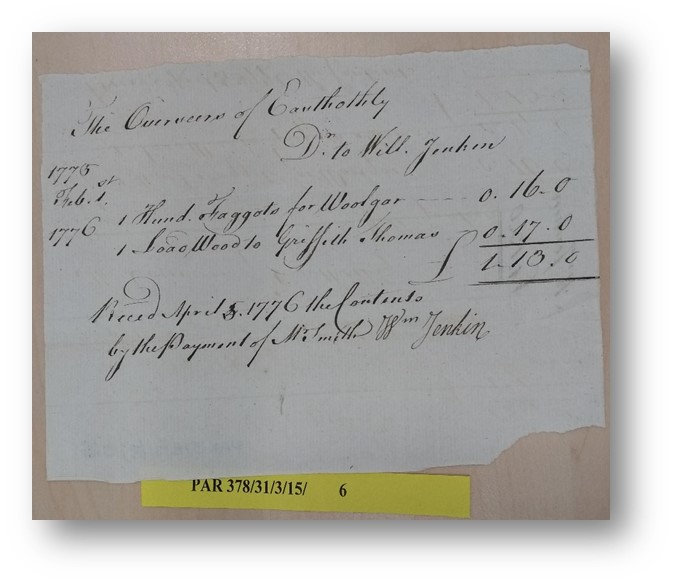

To fill these gaps to bursting, the project draws on a previously neglected class of sources: thousands upon thousands of slips of paper archived in Cumbria, Staffordshire and East Sussex, often tightly folded or rolled, of varying degrees of legibility, and all in the perplexing loops and waves of an eighteenth century hand …

These Overseers’ vouchers – similar to receipts – record the supply of food, clothes, healthcare, and other goods and services. Glimpse by glimpse, cross-reference by cross-reference, these fine-grained fragments glom together, revealing ever larger and more refined images of forgotten lives. Who was working at which dates? How did procurement and price fluctuate? What scale of income was possible for the suppliers the parish employed? What goods were stocked? Who knew whom, and when? Who had what? What broke or wore out when? As well as the digital database itself, the project will generate a dictionary of partial biographies, collaboratively authored by professional academics and volunteer researchers.

Louise took us through the data capture tool used by volunteer researchers. A potentially intimidating fifty-nine fields subtend the user-friendly front-end. The tool is equipped with several useful features. For example, it is possible to work remotely. The researcher has the option to “pin” the content of a field from one record to the next. The database automatically saves every iteration of each record. The controlled vocabulary is hopefully flexible enough to helpfully accommodate any anomalies. It’s also relatively easy to flag up records for conservation assessment or transcription assistance, or to go back and edit records. Right now they’re working on implementing automated catalogue entry creation, drawing on the Calm archive management system.

Personally, one of the things I find exciting about the project is how it engages both with the history of work and with the future of work. Part of its core mission is to illuminate institutions of disciplinarity, entrepreneurship, and precarity in eighteenth and early nineteenth century England. At the same time the project also involves, at its heart, questions about how we work in the twenty-first century.

Just take that pinning function, which means that researchers can avoid re-transcribing the same text if it’s repeated over a series of records. It almost feels inadequate to frame this as a “useful feature,” with all those overtones of efficiency and productivity! I’m not one of those people who can really geek out over user experience design. But most of us can relate to the experience of sustained labour in slightly the wrong conditions or using slightly the wrong tools. Most of us intuit that the moments of waste woven into such labour can’t really be expressed just in economic terms. And I’m pretty sure the moments of frustration woven into such labour can’t be expressed in purely psychological terms either. Those moments might perhaps be articulated in the language of metaethics and aesthetics? – or perhaps they need their very own (as it were) controlled vocabulary. But whatever they are, I think they manifest more clearly in voluntary labour, where it is less easy to let out that resigned sigh and think, “Whatever, work sucks. Come on Friday.”

I don’t have any first-hand experience of working with this particular data capture tool. But from the outside, the design certainly appears broadly worker-centric. I think digital work interfaces, especially those inviting various kinds of voluntary labour, can be useful sites for thinking more widely about how to challenge a productivity-centric division of labour with a worker-centric design of labour. At the same time, I guess there are also distinctive dangers to doing that kind of thinking in that kind of context. I wouldn’t be surprised if the digital humanities’ love of innovation, however reflexive and critical it is, tempts us to downplay the importance of the minute particularity of every worker’s experience, and the ways in which working practices can be made more hospitable and responsive to that particularity. (Demos before demos, that’s my demand).

I asked Louise what she thought motivated the volunteer researchers. Not that I was surprised – if something is worth doing there are people willing to do it, given the opportunity! – but I wondered what drew these particular people to this particular work? In the case of these parishes, it helps that there are good existing sources into which the voucher data can be integrated, meaning that individual stories are coming to life especially rapidly and richly-resolved. Beyond this? Obviously, the motives were various. And obviously, once a research community was established, it has the potential to become a motivating energy in itself. But Louise also reckoned that curiosity about these histories – about themes of class, poor relief and the prehistory of welfare, social and economic justice, and of course about work – played a huge role in establishing it in the first place.

Blake wrote in Milton about “a moment in each Day that Satan cannot find / Nor can his Watch Fiends find it.” I bet there is a moment within every rote task that those Watch Fields have definitely stuck there on purpose. It’s that ungainly, draining, inimitable moment that can swell with every iteration till it somehow comes to dominate the task’s entire temporality. It is politically commendable to insist that these moments persist in any task designed fait accompli from a distance, by people who will never have to complete that task more than once or twice … no matter how noble or comradely their intentions. But even if we should be careful about any dogmatic redesign of labour, I think we should at least be exploring how to redesign the redesign of labour. Karl Marx wrote in his magnum opus The Wit and Wisdom of Karl Marx that, unlike some of his utopian contemporaries, he was not interested in writing recipes for the cook-shops of the future. In some translations, not recipes but receipts. It actually is definitely the future now. And some of us are hungry.

JLW

The Poor Law: Small Bills and Petty Finance 1700-1834 is an AHRC-funded project.

- PI: Alannah Tomkins (Keele)

- Co-I: Tim Hitchcock (Sussex)

- Research Fellow: Louise Falcini (Sussex)

- Research Associate: Peter Collinge (Keele)