Everyone is talking about the season finale. Tomorrow at 3pm in the lab, Sharon Webb and Anna Maria Sichani will be giving the last in this run of Digital Methods Open Workshops, on the topic data modelling. All are welcome, and there are still places available.

Meanwhile, maybe it’s worth a quick catch-up? So here are few no-nonsense notes from Sharon Webb and Adam Harwood’s absolutely brimming SHL Open Workshop in April, on the topic of creating and publishing research data.

What is research data?

Sharon started us off. Who should think about publishing research data? Everybody! Yes, you humanities researcher. Data is not just numbers. Of course, what counts as research data varies considerably across different subjects, methodologies, topics, backgrounds, and habits. Some classic examples of research data-sets might be a set of measurements, or interview recordings and transcripts … but it’s also worth thinking more imaginatively and speculatively about what constitutes your research data.

One working definition of data might be all the relatively raw information you generate as a researcher in your processes of abstraction and categorization. Formally, that might include text documents (PDF, Word, RTF), spreadsheets, databases, posters, slide decks, sound recordings of field interviews, online lectures, recordings of engagement and knowledge exchange events, podcasts. That might include software, art, music. That might include metadata — data about data.

It got me thinking … do I have research data I don’t even know about?

Why publish it?

What do you encounter, and what processes do you follow, that might be useful to preserve and document for future research? Where might there be opportunities for citation, for citizen research, for collaboration, for audit and validation? What new research might it make possible? What new research might it inspire? Even, perhaps, what creative and artistic interventions? There is a slightly subversive and democratic aspect to all this: making the data public benefits independent researchers. This was one of the real revelations of the workshop for me: just how much fascinating information is already publicly available.

There is of course a slightly more straightforward and pragmatic aspect to all this: the UKRI funding bodies now ask for a data management plan. For example, an AHRC standard route grant will require a data management plan “for grants planning to generate data (3 A4 pages maximum).” The AHRC have recently done away with their technical plan requirement. Other funders (e.g. Marie Curie) ask for a technical plan, and there may be an assumption that any data management considerations will be included there.

Funders don’t generally accept the sentence, “My data is available on request.” Of course, there may be legitimate reasons for not making data available. Researchers should be aware of GDPR and the Data Protection Act. “Personal data” means any information relating to an identified or identifiable living individual. DMP Online structures the process of writing a data management plan, drawing on the specific guidance of the chosen funding bodies.

And, fwiw, Sussex also has a policy — “research data should be made freely and openly available with as few restrictions as possible in a timely and responsible manner […] regardless of whether or not the research is externally funded.” That said, there isn’t an actual Research Data Management Police Force roaming campus, as far as we’re aware.

How should I publish it?

One thing to consider is when you will deposit your data. Around grant writing proposal stage, it’s good to build in some time to actually prepare and deposit it. It can be a big chunk of work to get research data ready to be ingested by repositories. It’s not all mindless/mindful gruntwork either: there can be thorny questions around how to curate your data to make it useful for others and for long-term preservation. I can imagine there might be some interesting cross-disciplinary issues arising, and questions about how the framing of data blurs into its analysis and interpretation.

And where to deposit data? “Figshare Sussex probably,” seems to be the short answer. More broadly, it depends who you are affiliated with, and what their policies are. The Research Data Management service (a work-in-progress) may also answer some questions. There are institutional repositories, big generalist repositories, and domain-specific repositories, and there are different governance and funding models (i.e. public vs. commercial). Here are some handy links:

- UKDataArchive, funded by the ESRC, is “the UK’s largest collection of digital research data in the social sciences and humanities.”

- re3data.org is a database of repositories (incomplete, but filled with good starting points).

- FAIRsharing is another database of repositories, with more of a sciences and medicine emphasis.

- The Journal of Open Humanities Data features peer-reviewed articles describing data and methodologies with high re-usability.

- Zenodo is an open-access repository from CERN and the OpenAIRE program, with some similarities to Figshare. It runs on open source software (also called Zenodo).

- Then there’s Figshare, of which Figshare Sussex is a part.

All Figshare content will be assigned a DOI; CC BY 4.0 is the default license. Figshare also allows you to create and share ‘Collections,’ bringing together relevant datasets (whether or not they’re yours). What you upload to Figshare Sussex will get sucked up to Figshare mothership, which is indexed by Google.

You can also put on an embargo, a fact that for some reason gave me a lovely frisson of melodrama, “My data shall not be available … for ONE HUNDRED YEARS,” etc., and you can generate private links to share VIP access to embargoed data.

Your data will be backed up to Arkivum, which meets another common funding requirement, that the data will be preserved beyond the lifetime of the project. Arkivum keeps your data in three separate geographical locations. It doesn’t do file format shifts yet, but as part of The Perpetua Project (ominous energy), it eventually will do file format shifts as well.

Further background

The RCUK Concordat on Open Research Data explains precisely what open research data is, and what researchers can do to make their data open and freely accessible. It’s a long document, and Adam picked out a few key bits. The Concordat asserts the right of the creators of research data to reasonable first use. Support for development of appropriate data skills is recognised as a responsibility of all stakeholders — the university has a responsibility to provide useful services (which in our case is Figshare Sussex, as well as the emerging Research Data Management service).

Adam also touched on the FAIR Data Principles, originally intended for the sciences, but now with much wider adoption. Data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Re-usable. These are criteria you can measure your data against toward the end of a research project.

We ended with a whirlwind tour of metadata from Sharon. ‘Metadata is a (love) letter to the future — it makes explicit how “things” can be used.’ Anne Gilliland: ‘In general, all information objects, regardless of physical or intellectual form they take, have three features — content, context, and structure — all of which should be reflected through metadata.’ We had a little look at the Dublin Core standard, on which Figshare is based (if you’re going to add fields of your own, it would be best practice to align them to Dublin Core) and a case study, the Re-animating Data Project (70+ interviews carried out in 1989).

I left with a grateful heart and and a brimming brain, forgetting to sign in again. And also a vague unease. I got to thinking about all the data exhaust I leave behind, in the course of my research and my “research,” all the behavioural surplus I scarcely control and could never deposit, and yet which is deposited somewhere in the marketplace of personal data.

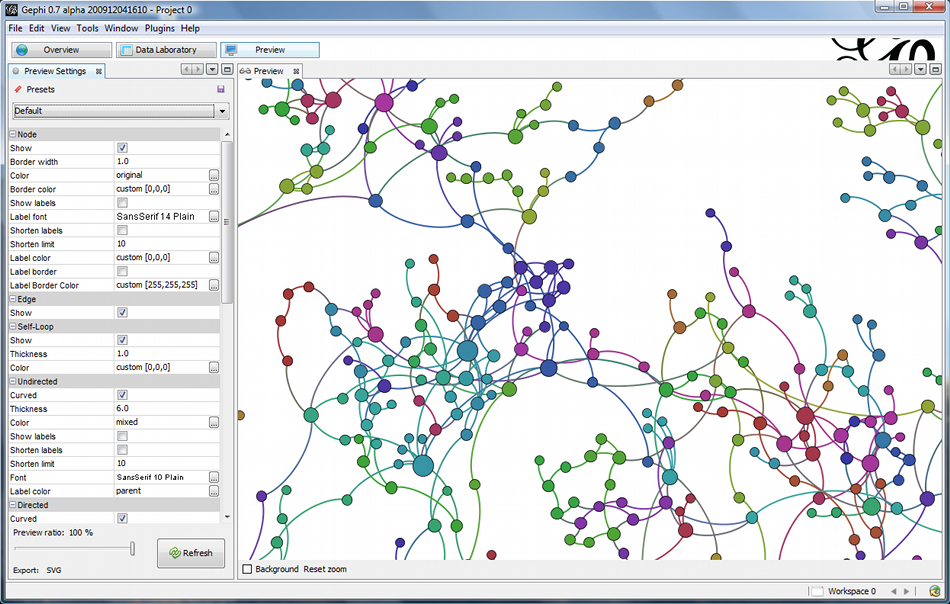

And I was thinking about how data at scale tends to disclose more than ever intended. Data analytics discover patterns that can be used as knowledge, and whose status as knowledge is often undecidable in the contexts in which they are used. I was thinking of those robots and researchers who can gaze hungrily at the “About Me” section of your social media profile, seeing not your attempt at self-expression, but only trait correlation with lemma term-frequency–inverse document-frequency (or whatever). Tech giants have learned the art of growing tall and fat on data crumbs; what will they do with data feasts?